U.S.-China Trade War Intensifies as Tariff Escalation Looms

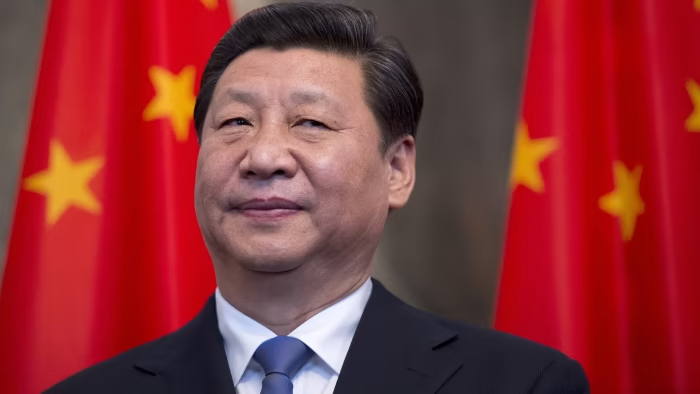

The trade standoff between the world’s two largest economies is escalating, with no signs of slowing. Just hours after U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to nearly double tariffs on Chinese imports, Beijing vowed to “fight to the end.”

If implemented, the proposed U.S. tariffs could subject most Chinese imports to a staggering 104% tax, representing a sharp escalation in the ongoing trade war. The looming deadline for the new tariffs—set to take effect Wednesday—raises the stakes for both sides.

Key Chinese exports to the U.S., such as smartphones, laptops, lithium-ion batteries, toys, and gaming consoles, are in the crosshairs. But the impact would go far beyond consumer electronics, extending to everyday goods like screws, boilers, and industrial components.

A High-Stakes Game of Chicken

With both countries digging in, the question remains: Who will blink first?

“It would be a mistake to think that China will back off and remove tariffs unilaterally,” said Alfredo Montufar-Helu, senior advisor at The Conference Board’s China Center. “Not only would it make China look weak, but it would also give leverage to the U.S. to ask for more. We’ve now reached an impasse that will likely lead to long-term economic pain.”

Global financial markets have reacted sharply. Last week’s announcement triggered a massive selloff, with Asian stocks suffering their worst drop in decades. While there was a slight recovery on Tuesday, uncertainty remains high.

Tit-for-Tat Tariffs Spread Across Asia

China has responded with retaliatory tariffs of 34%, while President Trump has warned of an additional 50% increase if Beijing doesn’t yield. More tariffs—some exceeding 40%—are scheduled to take effect this week, impacting not just China but other key Asian economies. Tariffs on goods from Vietnam and Cambodia could spike to 46% and 49% respectively.

Global Ripple Effects

Economists and analysts warn that the speed and scale of these tariff hikes are outpacing the ability of governments, businesses, and investors to adapt. With supply chains stretched across continents, the consequences of these rapid shifts could reshape global trade dynamics for years to come.

How is China responding to the tariffs?

China had responded to the first round of Trump tariffs with tit-for-tat levies on certain US imports, export controls on rare metals and an anti-monopoly investigation into US firms, including Google.

This time too it has announced retaliatory tariffs, but it also appears to be bracing for pain with stronger measures. It has allowed its currency, the yuan, to weaken, which makes Chinese exports more attractive. And state-linked enterprises have been buying up stocks in what appears to be a move to stabilise the market.

The prospect of negotiations between the US and Japan seemed to buoy investors who were fighting to claw back some of the losses of recent days.

But the face-off between China and the US – the world’s biggest exporter and its most important market – remains a major concern.

“What we are seeing is a game of who can bear more pain. We’ve stopped talking about any sense of gain,” Mary Lovely, a US-China trade expert at the Peterson Institute in Washington DC, told the BBC’s Newshour programme.

Despite its slowing economy, China may “very well be willing to endure the pain to avoid capitulating to what they believe is US aggression”, she added.

Shaken by a prolonged property market crisis and rising unemployment, Chinese people are just not spending enough. Indebted local governments have also been struggling to increase investments or expand the social safety net.

“The tariffs exacerbate this problem,” said Andrew Collier, Senior Fellow at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at Harvard Kennedy School.

If China’s exports take a hit, that hurts a crucial revenue stream. Exports have long been a key factor in China’s explosive growth. And they remain a significant driver, although the country is trying to diversify its economy with high-end tech manufacturing and greater domestic consumption.

It’s hard to say exactly when the tariffs “will bite but likely soon,” Mr Collier says, adding that “[President Xi] faces an increasingly difficult choice due to a slowing economy and dwindling resources”.

It goes both ways

But it’s not just China that will be feeling the impact.

According to the US Trade Representative office, the US imported $438bn (£342bn) worth of goods from China in 2024, with US exports to China valued at $143bn, leaving a trade deficit of $295bn.

And it’s not clear how the US is going to find alternative supply for Chinese goods on such short notice.

Taxes on physical goods aside, both countries are “economically intertwined in a lot of ways – there’s a massive amount of investment both ways, a lot of digital trade and data flows”, says Deborah Elms, Head of Trade Policy at the Hinrich Foundation in Singapore.

“You can only tariff so much for so long. But there are other ways both countries can hit each other. So you might say it can’t possibly get worse, but there are many ways in which it can.”

The rest of the world is watching too, to see where Chinese exports shut out of the US market will go.

They will end up in other markets such as those in South East Asia, Ms Elms adds, and “these places [are dealing] with their own tariffs and having to think about where else can we sell our products?”

“So we are in a very different universe, one that is really murky.”

How does this end?

Unlike the trade war with China during Trump’s first term, which was about negotiating with Beijing, “it’s unclear what is motivating these tariffs and it’s very hard to predict where things might go from here,” says Roland Rajah, lead economist at the Lowy Institute.

China has a “wide toolkit” for retaliation, he adds, such as depreciating their currency further or clamping down on US firms.

“I think the question is how restrained will they be? There’s retaliation to save face and there’s pulling out the whole arsenal. It’s not clear if China wants to go down that path. It just might.”

Some experts believe the US and China may engage in private talks. Trump is yet to speak to Xi since returning to the White House, although Beijing has repeatedly signalled its willingness to talk.

But others are less hopeful.

“I think the US is overplaying its hand,” Ms Elms says. She is sceptical of Trump’s belief that the US market is so lucrative that China, or any country, will eventually bend.

“How will this end? No-one knows,” she says. “I’m really concerned about the speed and escalation. The future is much more challenging and the risks are just so high.”